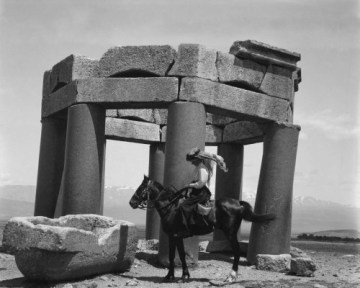

If there has ever been a historical figure readymade for a biographical documentary, it’s Gertrude Bell (1868-1926): archaeologist, explorer, spy, British political powerhouse, and the uncrowned ‘Queen of the Desert’. Hers is a story that requires no Hollywoodisation, and Letters from Baghdad lends almost none. In a bold approach, directors Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum rely on the writings and photographs of Bell herself, alongside contemporary film footage and correspondence, to tell the remarkable tale of a pioneering woman who went from the Thames to the Euphrates and became, through her own self-determination, the most influential woman in the British Empire in her era.

Bell’s writing is lyrical and informative, and the curated archive material – the fruit of over 1,600 letters by Bell, thousands of photographs, and some 500 hours of film, much of it rescued from obscurity and digitalised for the first time – is transformative. The documentary thus feels like an avalanche of historical material, a tactile and immersive experience across the mythologised sandscapes of Arabia.

The difficulty for the viewer, though, is following the plot. While the archival documents provide a richness of Bell’s character – she was at once at home on the back of a dirty camel and a lover of upper-class trappings, beloved by tribal men, and often considered unattractive and difficult by her European companions – the letters themselves don’t always provide enough context. It is too easy to get lost between this or that desert trip or diplomatic mission, and the passing references to titans like archaeologist Leonard Woolley and Major-General Percy Cox are in danger of going unnoticed by less-historically informed viewers.

The strength of the film’s narrative – Bell’s growing political influence despite her constant fight against sexism – also reflects the directors’ interests often, unfortunately for CWA readers, at the expense of her archaeological scholastic achievements. The ancient Middle East was not just fleeting fascination for Bell, part of the whirlwind of first loves in the region, nor simply a hobby to turn to following her dwindling political role. Bell threw herself at her archaeological work at all stages of her life, and the weight of her publications and photographs is still felt across the discipline. For example, though Bell’s interest in the site of Ukhaidir (central Iraq) is mentioned once, as if part of a traveller’s scrapbook, she actually systematically recorded it and spent two years collecting comparative evidence in Rome and elsewhere in Mesopotamia in order to appropriately date and understand it. Likewise, the creation of the Baghdad Archaeological Museum was her last major objective before her death via sleeping pill overdose at age 58, but it is no minor footnote for the finale.

Nevertheless, the film is intriguing, left rough with contrasting accounts and unequal emphases, as history should be in some respects. It certainly represents a colossal research achievement, and manages to forgo completely the temptation to employ modern talking head historians to simplify Bell’s life transitions.

If you have any interest in the colonial Middle East, the development of Iraqi archaeology, or trials of a stubborn but fiercely independent woman in a world betting against her, you will enjoy this film, even if its story feels slightly incomplete.

Review: Nicholas Bartos

Images: Courtesy of Verve Pictures