In 1703, Robert Drury, aged 16, was shipwrecked on the south coast of Madagascar. For the next 13 years he was a slave on the island, a ‘red’ slave because the people of Madagascar saw the skin colour that today we call ‘white’ as being ‘red’. Eventually he was able to escape and hitched a lift on a passing slaver and eventually arrived back in London. In 1729 he published a journal of his adventures. Such journals were at the time very fashionable, the most successful being that of Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe. By the late 19th century, people began to wonder whether in fact Robert Drury’s Journal was essentially a work of fiction like Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Now, in In Search of the Red Slave, Shipwreck and Captivity in Madagascar, Mike Parker Pearson and his co-author and co-researcher, anthropologist Karen Godden, argue that it is all true.

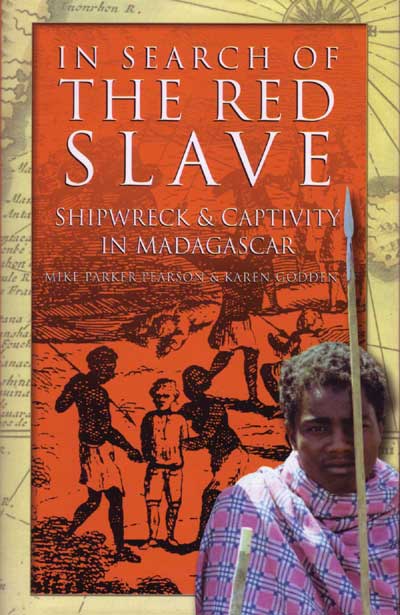

In 1703, Robert Drury, aged 16, was shipwrecked on the south coast of Madagascar. For the next 13 years he was a slave on the island, a ‘red’ slave because the people of Madagascar saw the skin colour that today we call ‘white’ as being ‘red’. Eventually he was able to escape and hitched a lift on a passing slaver and eventually arrived back in London. In 1729 he published a journal of his adventures. Such journals were at the time very fashionable, the most successful being that of Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe. By the late 19th century, people began to wonder whether in fact Robert Drury’s Journal was essentially a work of fiction like Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. Now, in In Search of the Red Slave, Shipwreck and Captivity in Madagascar, Mike Parker Pearson and his co-author and co-researcher, anthropologist Karen Godden, argue that it is all true.

To the archaeologist, Madagascar is a very interesting island. Although it lies only 300 miles off the east coast of Africa, it was uninhabited until around two thousand years ago, when it was settled by immigrants from Indonesia, 2,000 miles away across the Indian Ocean, – the language spoken on Madagascar is still a branch of the Indonesian languages. However, Mike Parker Pearson, now Professor of Archaeology at Sheffield University, became interested in it for a different reason: the inhabitants still bury their dead in what can only be called long barrows. Today these consist of two long parallel walls, often decorated with modern graffiti – in one case a picture of Elvis Presley – but with an infill of large boulders covering the coffin in which the dead are laid to rest. The burial procedure is often a long drawn out process lasting three months or more, for that is the time it takes to acquire the wherewithal to purchase the cattle which are slaughtered for the funeral feast. To the archaeologist of Neolithic Britain, Madagascar is paradise.

However, in reconstructing the history/archaeology of Madagascar, Robert Drury’s journal is of prime importance, a first hand account of life in the early 18th century. But is it genuine or is it essentially a work of imagination? It is certainly not in Defoe’s style or written with Defoe’s alluring genius. Its politics are not those of Defoe either; Defoe was a Whig and what was worse, a Dissenter – this gives his novels their bite – whereas Drury was apolitical perhaps even Tory. Could archaeology help solve the problem of the Journal’s genuineness? Would it be possible archaeologically to reconstruct Drury’s geography? For nearly a decade this became the framework for Mike’s fieldwork, and in this new book, Mike Parker Pearson and his co-author and co-researcher, anthropologist Karen Godden, tell the story of their researches. The book is an alluring amalgam of their researches into piracy, trade and slavery (all three mixed together in the early 18th century) together with the archaeology and history of Madagascar, and most of all, the story of their own expeditions.

The conditions of their research were appalling. They were researching the southern coast of the island which is the most infertile and traditionally given over to cattle breeding rather than rice growing. It is covered by prickly scrub, numerous varieties of bugs and poor water supplies. However, by the time they arrived, the basic pottery sequence had already been worked out, and so their major activity was field walking, covering vast areas to look for pottery scatters. This meant that instead of doing what most anthropologists do and sitting in one place and making friends with the locals, they constantly had to move on, constantly reassuring the inhabitants that they were friendly, harmless, if in fact like most archaeologists, more than a little mad.

Eventually, they achieved total success, they located a large pottery scatter which could plausibly be identified as the place where Robert Drury spent most of his time as a slave. Several of the places that he mentioned were also identified, and even the site of the shipwreck – which proved to be surprisingly easy, as once they began making inquiries, the native inhabitants knew of a place where two cannon could still be seen half covered by the sand.

This is a splendid new book that makes a fascinating read. It could do with a few more illustrations, and in particular with some more maps. From a historical point of view, a more revisionist view of piracy and slavery would have been refreshing: Robert Drury after all survived and even throve for a decade or more as a slave, owning his own property, and even being expected to join the army and carry an ancient musket when his tribe went to war with a neighbouring tribe. He captured the Prince’s wife and attractive daughter: he gave the wife to his master (who returned her), but was allowed to keep the 16-year old daughter as his wife. Perhaps one should call him a serf rather than a slave – the whole concept of slavery needs refining. But this is an alluring book bringing together many different aspects into a satisfying whole.

This article is an extract from the full article published in World Archaeology Issue 13. Click here to subscribe